Living with Risk

- simonavaglieco

- Jun 10, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2020

The novel coronavirus crisis forced us to ask how we assess risks and more importantly, how we learn to live with uncertainty.

We have been living safely for most of our lives. All of a sudden, the pandemic quickly reminded us that most of our daily activities imply a sort of risk-taking. Some of these were so routine that we stopped thinking they have a certain degree of risk. We cross the street (more often than not without looking at the traffic light), get on a plane, take small gambles in the kitchen without spending time analysing losses or possible gains of our actions. These have already been accounted for in the back of your mind.

When we are faced with a new risk, we quickly reconnect to our most basic instinct: we retreat, wait, think and start to go through the pros and cons of venturing out. If we add to this a certain emotional involvement (being fear for our life or our livelihood), it gets all more complicated. We end up spending more time evaluating and calculating that eventually, we feel stuck. As a transition coach, this is where I usually meet my clients. Some have been agonising for a long time about what to do next. Others have already taken a decision but can't follow through with it—the risk of losing outweighs possible gains.

Risk-taking has been described as " the appraised likelihood of negative outcome for behaviour" and how we perceive risk is influenced by our experience, our values.

If taking risky decisions can be complicated, how would it feel like to live with the risk?

Any change brings along a certain degree of risk. Sometimes the calculation is easily (although painfully) made: in the case of the coronavirus crisis- the potential death of a hundred thousand carried a heavier weight than the "economic deaths"; other times the stakes are not so high or well defined. Risk-taking has been described as " the appraised likelihood of negative outcome for behaviour" (Marvin Zuckerman) and how we perceive risk is influenced by our experience, our values.

If taking risky decisions can be complicated, how would it feel like to live with the risk?

I asked around. Some like the adrenalin surge, the challenge posed by "problem-solving". Some people create dares for themselves so they can fight off the boredom. The most common answer I received was "get to know your enemy."

Luke knows that it is impossible to predict events. So he concentrates on what is within his control. Aware of the risks, he covers all possible ground but ultimately what makes the decision possible for him is " the feeling that whatever the outcome, I will find a way to make it work".

Luke, a partner in a software firm, said that risk assessment is part of his daily routine in his company. Innovation and keeping ahead of the game requires quick decisions, ideally the right ones. For him, the most important thing is to be prepared to cover all possible risks. Drawing on his experience, he "wargames" all possible outcomes. Then he takes the plunge. "I dissect the risk, but when it comes to making the decision, I close my eyes, and I go for it". Luke knows that it is impossible to predict events. So he concentrates on what is within his control. Aware of the risks, he covers all possible ground but ultimately what makes the decision possible for him is " the feeling that whatever the outcome, I will find a way to make it work". Luke's confidence stems from an in-depth knowledge of his product. " After 20 years, I know what I do inside out. Over time I started to look at setbacks more as opportunities when I can learn how to do what I do better."

Knowledge, the sense that there is always a way around possible unwelcome outcomes: a focus on learning and a "mastery" approach where contribution rather than performance is valued are quite often the ingredients of success stories.

Similarly, in an interview with Forbes in 2017, Captain Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger mentions situational awareness as a way to manage risks.

"Bad outcomes are rarely the result of a single failure but are instead the end result of a chain of events, and when we sensitise ourselves to risk and are able to identify it proactively, we can break the chain and have a good outcome."

Sully, the captain famous for safely landing a plane on the Hudson River, worked for years to create a culture of collaboration, teamwork and change of behaviour that with technology advancement made flying much safer. His knowledge of processes together with the skills that came with his training as a pilot ("discipline, diligence, dedication, and intellectual curiosity..") is what helped him to frame his decision on that fateful day in January.

"...one way of looking at it was that for 40 years I had made small regular deposits in this bank of education, training and experience and on January 15th 2009, the balance was sufficient that I could make a sudden large withdrawal."

Learning how to negotiate risk effectively also has far-reaching benefits. It allows us to explore opportunities we would otherwise ignore but also provide us with a stage for learning and testing our creativity and inventiveness, ultimately boosting our confidence.

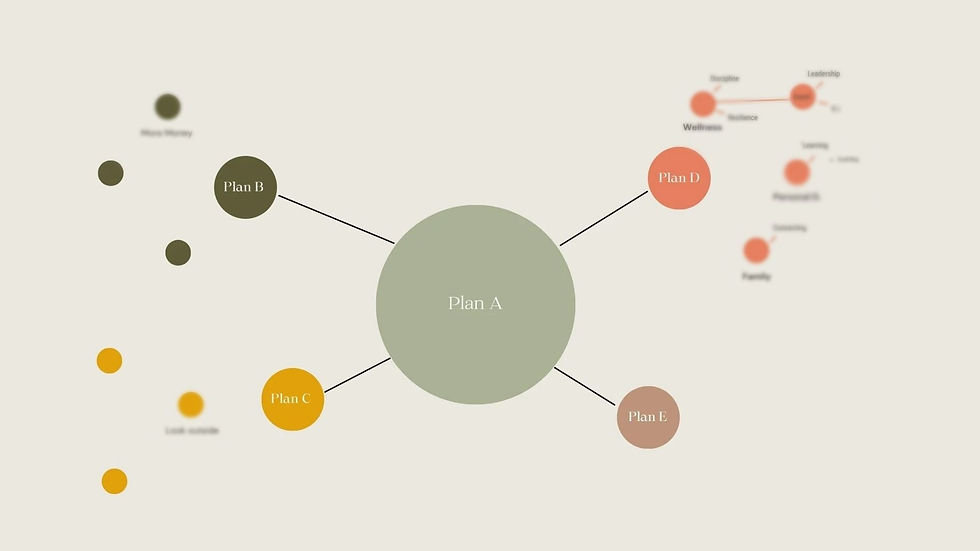

When we drive a car or cross the street, or work on house improvements, we instinctively use the same skills mentioned by Luke and Capitan Sully. Living with an unknown risk is not different, although we tend to focus more on the risk itself rather than on how to manage it. This is where coaching can make a big difference. It can support us in organising a mental model of our reality; make us aware of the tools we have to navigate it. Most crucially it can reconnect us with a deep sense of confidence - a belief that we can trust ourselves to do our best in all circumstances.

Learning how to negotiate risk effectively also has far-reaching benefits. It allows us to explore opportunities we would otherwise ignore but also provide us with a stage for learning and testing our creativity and inventiveness, ultimately boosting our confidence.

Risk-averse is a well-known term to describe the propensity to overlook gains when faced with the possibility of a loss. Coming out of a "lockdown" be it an enforced or a voluntary one, can pose all kinds of problems. Still, the consequences of playing it safe could be dramatic: for companies, it could spell the end of their existence; for individuals, it could mean stagnation and most dramatically could increase the risk of becoming redundant in a society subject to continuous and unpredictable change.

Comments